On Making Art In The Absence Of Hierarchy

An interview with 'The Surrender of Man' author and Archway Editions editor Naomi Falk.

By

“In moments of darkness I gravitate toward art,” Naomi Falk begins The Surrender of Man, her forthcoming essay collection from Inside the Castle Press, out April 22.

A series of dreamlike introspections on the works of artists like Remedios Varo, Elia Bianchini, Helen Frankenthaler, Juan Antonio Olivares, Shiva Ahmadi, and Ryan Bock, among others, Falk meditates on the synchronous connection between art, death, and their ability to inspire the written word.

“The writing and art I love tends to ask a question rather than answer one,” writes Falk, whose tastes have been honed through her work at emerging galleries, major institutions like MoMA, and her current position as an editor at the independent press Archway Editions. In a world where the state of literature and art can feel fraught—thanks to the precarious monopolization of publishing houses and rising illiteracy—Falk’s work is like a thunderous incantation to reawaken our collective consciousness and a call to creativity as healing space of human transcendence.

Ahead, Falk discusses her essays, the freedom of anti-capitalist institutions, the power of educators, blue periods, the majesty of Washington State, and more.

How did you go about curating the 20 different artistic works included in this book?

The process of writing this was like several cycles of birth and death, and the works just came up as I was writing. I had become extremely interested in writing about art around 2017. At the time, I was working at the Museum of Modern Art, and I was an editorial director for a gallery as a side passion project. I was trying to oversaturate myself with visual art. That said, this is not a book of my greatest hits. It’s about art that made me think over the process of writing, like an immersive project.

The structure itself was directly influenced by Olivia Lang’s Lonely City. Each of her chapters is about an artist, and she tied her own experience to their life at work and her experience of living in the city. It’s so beautifully done, and my work is indebted to that book.

You write about the difference between art-making within an institutional framework versus in an independent, DIY setting. Can you talk more about this concept?

It’s such a gift to be able to study at a university. But when it comes to work, careerism is like a goofy charade. I don’t think that it’s conducive to making the work you want to make. I respect people who want to have big books on the bestseller list, but I feel like it just gets in the way of saying what you want to say. At institutions, there’s the baseline that I’m expected to dress the part, and there are things you're expected to put up with that are unnatural. We all deal and cope. But I have a fear of losing myself. I experience so much more freedom to move when I work for structures that are less propelled by capitalism and less beholden to bureaucracy or a very strict sense of hierarchy.

Working for powerHouse books and Archway Editions now, it’s very free. It’s the most significant thing that’s ever happened to me in my life. We have the luxury of being independent. We sacrifice financial stability, but we don’t have a CEO who is worried about how many copies we’re going to sell. Instead, we say: What do we think we can bring to people that we like? Or that’s different? But I’m not passing judgement on other editors at all. I know of friends who have written some deeply interesting and experimental projects, and these amazing editors cannot get their bosses to agree to it.

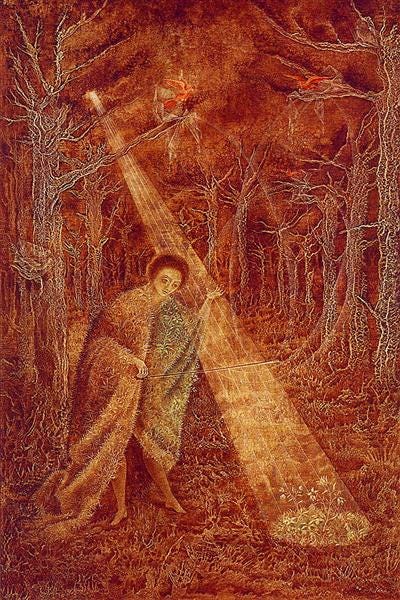

My favorite essay in the collection was the one about Remedios Varo and her oil painting, Solar Music. She and Leonara Carrington are serious inspirations for you. Can you tell me more about why?

She’s a cross-disciplinary thinker. Her artworks capture the things that are felt, but unseen, and without being tied to a particular sect of religion or school of thought. Her interests feel super archaic and transhuman, and her work feels most closely tied to my interests. It’s part of subculture in a way that felt true to me.

I love the way you write about educators: “I’d always worked hard for teachers who devastated me in one way or another, opening portals of depth and emotional complexity and introducing me to feelings beyond the ones I’d encountered in most of my daily life.” Great teachers can be sorcerer-like.

In the acknowledgements, I actually thank my high school English teachers. Teaching English, History, or whatever we call the Liberal Arts, is vulnerable.

In the book, I write about how I was taking a lit class and we were reading Pedro Paramo, which is one of my favorite books ever, and the professor started crying. She said it reminded her of when her sister died. There isn’t really another discipline where those kinds of stories come to light, and I think this is why people tend to form close relationships with their English teachers. I’ve always felt that way about mine, so it felt disingenuous to not include them in this book to some capacity.

This book is also about your childhood and what it meant to grow up in Washington. However, you write that Washington is, at times, difficult for you to grasp in your text, because you haven’t lived there permanently for years.

I love Washington so much, but it feels like stolen valor to keep writing about something that you’re not actually experiencing. It’s a hard line to tread. You look at it, and it has all of these weird curvatures and refracts light in different ways. But it’s also warped. Quickly, it can turn into nostalgia for “the good old days” that never actually existed.

Washington feels like this special other land to me. Twin Peaks, crop circles, aliens, Sasquatches. I don’t like the final frontier narrative, but I think it has a strange final frontierness. The light there is really strange and technicolor, and it’s also so green. Everything feels like it’s happening in this other dimension. When I’m home walking on the beach or through the rain forest on the peninsula, it feels like experiencing magic.

You mention experiencing “blue periods” a few times in the book. I read “blue periods” to mean a period of melancholy and moodiness. Whimsical, but also deadening.

Obviously, when you’re learning about art, you learn about Picasso’s Blue Period. Picasso’s art doesn’t particularly move me, but his Blue Period does because it stands out so much within the context of his work. The moments where the depression I experience is particularly rough, it’s not always because I’m going through something. It’s because I’m not able to see past what’s troubling me. It feels like there are concrete walls that are barring me from engaging with the things that I like.

That said, I’m interested in what gives us the ability to transition out of life’s difficult periods, especially creatively. As artists, it’s so important to think about these moments, collect them, and consider what it was that got us through. I feel like there are many transitionary moments of my life that I can relate directly with the artwork I’m interacting with, which is basically what this book is about.

Like the Alberto Giacometti piece in the book, The Palace At 4 AM, for example. I can name the time of day, the person I was talking to, and the things that were said in the moment of seeing that piece, which catalyzed me out of feeling like there was nothing redeeming about existence, or about my own life. Artwork is tethered to those moments. Artwork is the punctuation, the bookends to my blue periods.

Yesssssss

Incredible!!